Overview

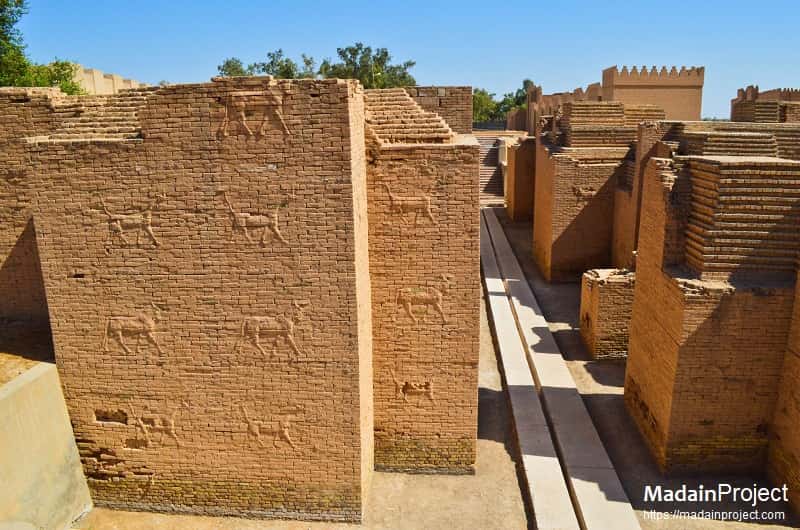

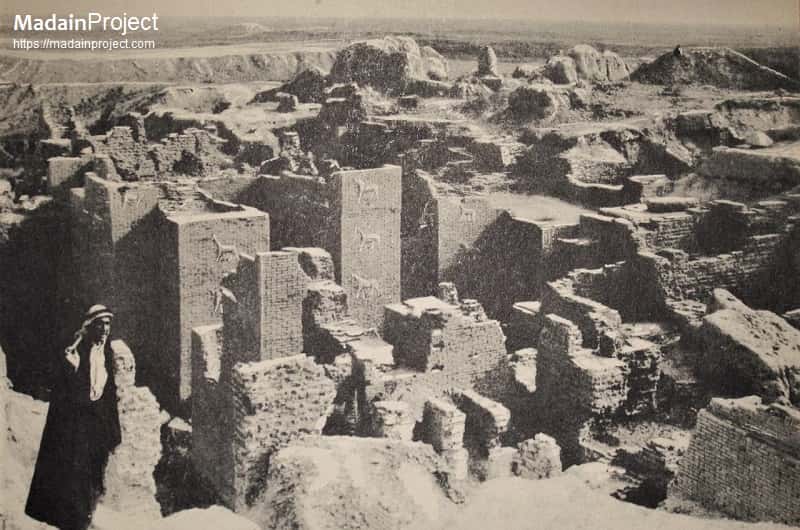

The decoration of the walls of the Ishtar Gate consisted of alternated figures of bulls and dragons (sirrush). They are placed in horizontal rows on the parts of the walls that are open to observation by those entering or passing, and also on the front of both the northern wings, but not where they would be wholly or partially invisible to the casual observer. Through the gate ran the Processional Way, which was lined with walls showing about 120 lions, bulls, dragons, and flowers on enameled yellow and black glazed bricks, symbolizing the goddess Ishtar. The gate itself depicted only gods and goddesses.

Architecture and the Archaeological Remains

circa 575 BCE

The rows are repeated one above another; dragons and bulls are never mixed in the same horizontal row, but a line of bulls is followed by one of sirrush. Each single representation of an animal occupies a height of 13 brick courses, and between them are 11 plain courses, so that the distance from the foot of one to the foot of the next is 24 courses. These 24 courses together measure almost exactly 2 metres, or 4 Babylonian ells, in height." see page 41

circa 575 BCE

The gates connected with the lower street levels bore these decorations as relief representations. At the two highest street levels, the gate had a facade of blue, glazed bricks, and the bulls and dragons were in different glazed colours, the uppermost ones even in relief. In an effort to illustrate this ancient site in a new way, the Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin and Google Arts & Culture have virtually reassembled Ishtar Gate (inspect), in its original location. This work of this project illustrates how the ancient landmark would have looked like before it was parted.

circa 575 BCE

King Nebuchadnezzar II ordered the construction of the gate and dedicated it to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. The gate was constructed using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-relief mušḫuššu (dragons), aurochs (bulls), and lions, symbolizing the gods Marduk, Adad, and Ishtar respectively. Parts of the gate and lions from the Processional Way are in various other museums around the world. Only four museums acquired dragons, while lions went to several museums.

circa 575 BCE

With Nebuchadnezzar II’s opulent reconstruction scheme of central Babylon many mudbrick buildings were replaced by ones of burnt bricks, the latter often much larger and on raised levels. At successive occasions the quay walls in the area of the palace and the Ishtar Gate were rebuilt further to the north and as they became incorporated to the northern walls of the palace under its expansion. During the reign of Nabopolassar and at the beginning of that of Nebuchadnezzar II, the Ishtar Gate was a normal double city gate of unbaked mudbrick like the rest of the double city walls including the other seven gates. The Street of Procession passed through the gate on the flat surface.

circa 575 BCE

The Ishtar Gate was part of the double wall of unbaked mudbricks framing the inner city. Originally the gate had also been of mudbrick and had been built on the same flat surface as the wall. The gate’s facades exhibited series of protective animals – bulls and dragons – that came to the encounter of those who entered. The front of the gate has a low-relief sculpted design with a repeated pattern of images of two of the major gods of the Babylonian pantheon.

circa 575 BCE

Depictions of Mušḫuššu (inspect) on Ishtar Gate, a mythological hybrid, it is a scaly dragon with hind legs resembling the talons of an eagle, feline forelegs, a long neck and tail, a horned head, a snake-like tongue, and a crest. The mušḫuššu is the sacred animal of Marduk and his son Nabu during the Neo-Babylonian Empire. It was taken over by Marduk from Tishpak, the local god of Eshnunna. Marduk was seen as the divine champion of good against evil, and the incantations of the Babylonians often sought his protection.

circa 575 BCE

The second god shown in the pattern of reliefs on the Ishtar Gate is Adad (also known as Ishkur), whose sacred animal was the aurochs (inspect), a now-extinct ancestor of cattle. Adad had power over destructive storms and beneficial rain. The design of the Ishtar gate also includes linear borders and patterns of rosettes, often seen as symbols of fertility.

circa 575 BCE

The bricks of the Ishtar gate were made from finely textured clay pressed into wooden forms. Each of the animal reliefs were also made from bricks formed by pressing clay into reusable molds. Seams between the bricks were carefully planned not to occur on the eyes of the animals or any other aesthetically unacceptable places. The bricks were sun-dried and then fired once before glazing. The clay was brownish red in this bisque-fired state.

Archaeological Context

circa 575 BCE

Several important buildings stood around the gate's interior, including the Ninmakh Temple to the east. The E-mah (great temple of Ninḫursaĝ) as seen from the west, looking over the Ishtar Gate in the bottom foreground. Currently the walls and roofs of the temple are in a very bad condition and no recent renovations have been done. Due to its use as military base by US the site has suffered extensive damage, according to a study by the British Museum, the damage was extensive: some 300,000 sq m (4,000 acres) was covered with gravel.

Reconstruction at the Pergamon Museum

circa 575 BCE

The reconstructed Upper facade of the ancient Ishtar gate is now displayed at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The external facade features two columns and five rows of depicted animals on two seperate panels on each side of the entrance portal. Rows on both panels from top to bottom depict aurochs, mušḫuššus, aurochs, mušḫuššus, aurochs respectively. This is only the top (nearly) half of the outer most gate (illustration).

Gallery

See Also

- Ishtar Gate (Overview)

- Ishtar Gate at Pergamon Museum

- Processional Street

- Inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II on Ishtar Gate

References

- MacFarquhar, Neil (August 19, 2003). "Hussein's Babylon: A Beloved Atrocity". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Stokstad, Marilyn (2018). Art History. Upper Saddle River: Pearson. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780134479279.

- British Museum Website Archived 2014-01-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Panel with Striding Lion". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2018.

- R.P.D. (October 1932). "The Lion of Ishtar". Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University. 4 (3): 144–147. JSTOR 40513763.

- Bernbeck, Reinhard (5 January 2009). "The exhibition of architecture and the architecture of an exhibition". Archaeological Dialogues. 7 (2): 98. doi:10.1017/S1380203800001665.

- King, Leo (2008). "The Ishtar Gate". Ceramics Technical. No. 26 (2008): 51–53. Retrieved 21 Nov 2017.

- Bilsel, Can (2012), Antiquity on display : regimes of the authentic in Berlin's Pergamon Museum, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-957055-3

- Bertman, Stephen (7 July 2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-0195183641.

- Maso, Felip (5 January 2018). "Inside the 30-Year Quest for Babylon's Ishtar Gate". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Clayton, Peter A.; Price, Martin (2013-08-21). The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9781136748103. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Marzahn, Joachim (1981). Babylon und das Neujahrsfest. Berlin: Berlin : Vorderasiatisches Museum. pp. 29–30.

- Kleiner, Fred (2005). Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Belmont, CA: Thompson Learning, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-15-505090-7.

- Bahrani, Zainab (2017). Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-500-51917-2.

- "Panel with striding lion | Work of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2017-11-28.